MONS, AND THE RETREAT

By Captain G. S. Gordon

With an Introduction by Field-Marshal Lord French

1/6 net.

The Evening News.—‘... The true history of those amazing and heroic days, briefly and clearly told by a soldier and an expert.’

THE MARNE CAMPAIGN

By Lieut. Col. F. E. Whitton, C.M.G.

10/6 net.

Saturday Review.—‘... Clear and concise ... gives a much better general impression of the Battle of the Marne than any other we know.’

1914

By Field-Marshal Viscount French of Ypres, K.P., O.M., etc.

With a Preface by Maréchal Foch

21/- net.

CONSTABLE AND CO. LTD., LONDON.

YPRES, 1914

AN OFFICIAL ACCOUNT PUBLISHED BY

ORDER OF THE GERMAN GENERAL STAFF

AN OFFICIAL ACCOUNT PUBLISHED BY

ORDER OF THE GERMAN GENERAL STAFF

TRANSLATION BY G. C. W.

WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY THE

HISTORICAL SECTION (MILITARY BRANCH)

COMMITTEE OF IMPERIAL DEFENCE

HISTORICAL SECTION (MILITARY BRANCH)

COMMITTEE OF IMPERIAL DEFENCE

LONDON

CONSTABLE AND COMPANY LTD

1919

CONSTABLE AND COMPANY LTD

1919

Printed in Great Britain

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

SKETCH MAPS IN TEXT

INTRODUCTION

The German book of which a translation is here given was written in the autumn of 1917 by Captain Otto Schwink, a General Staff Officer, by order of the Chief of the General Staff of the Field Army, and is stated to be founded on official documents. It forms one of a series of monographs, partly projected, partly published, on the various phases of the war, but is the only one that is available dealing with operations in which the British Army was engaged. Several concerned with the Eastern theatre of war have already appeared, and one other entitled ‘Liège-Namur,’ relating to the Western.

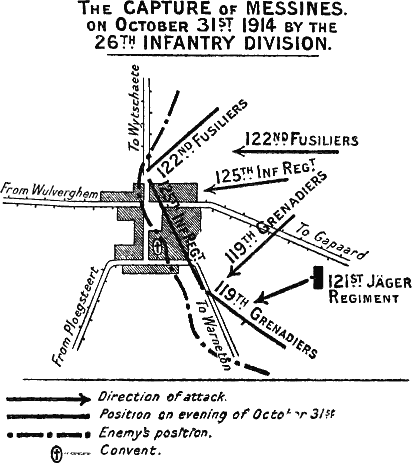

Field-Marshal Viscount French, in his book ‘1914,’ has said that the period 27th to 31st October during the first battle of Ypres was ‘more momentous and fateful than any other which I directed during my period of service as Commander-in-Chief in the field. 31st October and 1st November will remain for ever memorable in the history of our country, for during those two days no more than a thin and straggling line of tired-out British soldiers stood between the Empire and its practical ruin as an independent first-class Power.’ The German account accentuates the truth of Lord French’s appreciation of the great peril in which the Army and the Nation stood. It tells us of the enemy’s plans, and of the large forces that he brought up with great skill and secrecy to carry[Pg x] them out, and, generally, to use Marshal Foch’s expression, lets us ‘know what was going on in the other fellow’s house.’ But it does more than that: unconsciously perhaps, it bears convincing testimony to the fighting powers of the British Army, the determination of its leaders, the extraordinary effectiveness of the fire of its artillery and of its cavalry and infantry, and the skill of its engineers; for it repeatedly credits Field-Marshal Sir John French with ‘reinforcements in abundance,’ insists that our troops ‘fought desperately for every heap of stones and every pile of bricks before abandoning them,’ and definitely records that ‘the fact that neither the enemy’s commanders nor their troops gave way under the strong pressure we put on them ... gives us the opportunity to acknowledge that there were men of real worth opposed to us who did their duty thoroughly.’ We are further told that the effect of our artillery was such that ‘it was not possible to push up reserves owing to heavy artillery fire’; that ‘all roads leading to the rear were continuously shelled for a long way back’; that the German ‘advancing columns were under accurate artillery fire at long range’; that our shells ‘blocked streets and bridges and devastated villages so far back that any regular transport of supplies became impossible.’ As regards rifle and machine-gun fire, we are credited with ‘quantities of machine-guns,’ ‘large numbers of machine-guns,’ etc.; with the result that ‘the roads were swept by machine-guns’; and that ‘over every bush, hedge and fragment of wall floated a thin film of smoke betraying a machine-gun rattling out bullets.’ At that date we had no machine-gun units, and there[Pg xi] were only two machine-guns on the establishment of a battalion, and of these many had been damaged, and had not yet been replaced; actually machine-guns were few and far between. The only inference to be drawn is that the rapid fire of the British rifleman, were he infantryman, cavalryman or sapper, was mistaken for machine-gun fire both as regards volume and effect. Our simple defences, to complete which both time and labour had been lacking, became in German eyes ‘a well-planned maze of trenches,’ ‘a maze of obstacles and entrenchments’; and we had ‘turned every house, every wood and every wall into a strong point’; ‘the villages of Wytschaete and Messines ... had been converted into fortresses’ (Festungen); as also the edge of a wood nearGheluvelt and Langemarck. As at the last-named place there was only a small redoubt with a garrison of two platoons, and the ‘broad wire entanglements’ described by the German General Staff were in reality but trifling obstacles of the kind that the Germans ‘took in their stride,’[1] the lavish praise, were it not for the result of the battle, might be deemed exaggerated. Part of it undoubtedly is. It is fair, however, to deduce that the German nation had to be given some explanation why the ‘contemptible little Army’ had not been pushed straightway into the sea.

The monograph is frankly intended to present the views that the German General Staff wish should be held as regards the battles, and prevent, as their Preface says, the currency of ‘the legends and rumours which take such an easy hold on the popular imagina[Pg xii]tion and are so difficult, if not impossible, to correct afterwards.’ One cannot naturally expect the whole truth to be revealed yet; that it is not will be seen from the notes. The elder von Moltke said, when pressed by his nephews to write a true account of 1870-1—to their future financial advantage—‘It can’t be done yet. Too many highly placed personages (hohe Herrschaften) would suffer in their reputations.’ It was not until twenty-five years after the Franco-Prussian War that Fritz Hönig, Kunz and other German military historians who had been given access to the records, were allowed to draw back the veil a little. The publication of the French General Staff account began even later. What is now given to us is, however, amply sufficient to follow the main German plans and movements; but the difficulties that prevented the enemy from making successful use of the enormous number of troops at his disposal and his superior equipment in heavy artillery, machine-guns, aeroplanes, hand-grenades and other trench warfare material, are untold. Until we learn more we may fairly attribute our victory to the military qualities of the British, French and Belgian troops, and the obstinate refusal of all ranks to admit defeat.

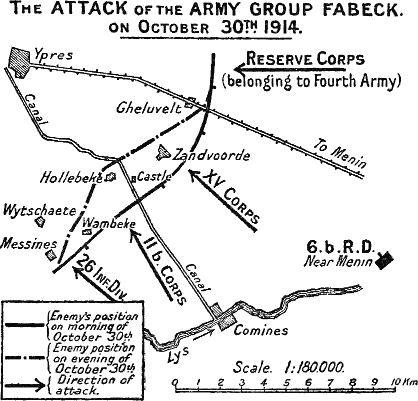

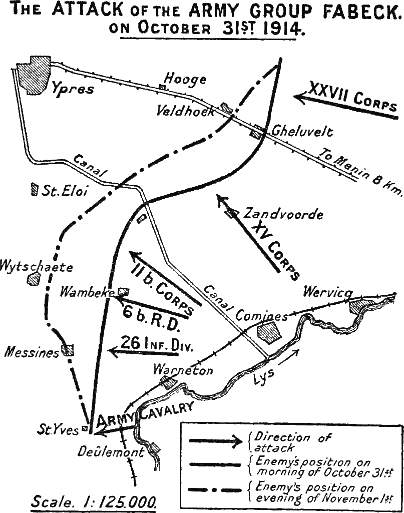

The German General Staff specially claim that the first battle of Ypres was a German victory, ‘for it marked the failure of the enemy’s intention to fall on the rear of our Western Armies, to free the rich districts of Northern France and the whole of Belgium,’ etc. etc. Granted that we did so fail, the battle can, on that General Staff’s own evidence, be regarded as a drawn one. For it is definitely stated in the monograph that the object of the operations was ‘successfully[Pg xiii] closing with the enemy ... and gaining Calais, the aim and object of the 1914 campaign’—this the German Army notoriously did not do. The intention to break through is repeatedly stated: ‘although fresh reinforcements had been sent up by the German General Staff ... a break-through had not been possible.’ ‘Another effort to break through should be made as soon as possible.’ We are told that Fabeck’s Army Group (eventually nine infantry and five cavalry divisions) was formed ‘as a strong new army of attack ... for breaking through on the front Werwicq-Warneton.’ Linsingen’s Army Group (five divisions) after the failure of von Fabeck was formed ‘to drive back and crush the enemy lying north of the (Comines-Ypres) canal ... and to break through there.’ Finally, however, it is admitted that ‘no break-through of the enemy’s lines had been accomplished.... We had not succeeded in making the decisive break-through, and the dream of ending the campaign in the west in our favour had to be consigned to its grave.’ In fact, the book is largely an apologia and a confession of failure which mere protestations of victory cannot alter.

The effects of a German victory on the course of the war, with the Channel ports in German hands, as compared with those of an Allied victory in Flanders, which at that period of the war and at that season of the year could have resulted in little more than pushing the enemy back into Belgium a few miles, may be easily imagined. If the battle was a tactical draw, at least we had a strategic balance in our favour.

The principal reasons advanced for the German ill-success are ‘the enemy’s numerical superiority,[Pg xiv] and the strength of his positions,’ and of course the drastic course taken by the Belgians of ‘calling in the sea to their aid.’

There is constant repetition of these pleas throughout the book. To those who were there and saw our ‘thin and straggling line’ and the hastily constructed and lightly wired defences: mere isolated posts and broken lengths of shallow holes with occasional thin belts of wire, and none of the communication trenches of a later date, they provoke only amazement. Even German myopia cannot be the cause of such statements.

As regards the superiority of numbers, the following appears to be the approximate state of the case as regards the infantry on the battle front from Armentières (inclusive) to the sea dealt with in the monograph. It is necessary to count in battalions, as the Germans had two or three with each cavalry division, and the British Commander-in-Chief enumerates the reinforcements sent up to Ypres from the II and Indian Corps by battalions, and two Territorial battalions, London Scottish and Hertfordshires, also took part. The total figures are:—

| British, French, Belgian | 263 battalions. |

| German | 426 battalions. |

That is roughly a proportion of Allies to Germans of 13 to 21. Viscount French in his ‘1914’ says 7 to 12 Corps, which is much the same: 52 to 84 as against 49 to 84, and very different from the German claim of ‘40 divisions to 25.’ Actually in infantry divisions the Allies had only 22, even counting as complete the Belgian six, which had only the strength[Pg xv] of German brigades. Any future correction of the figures, when actual bayonets present can be counted, will probably emphasise the German superiority in numbers still more, and the enemy indisputably had the advantage of united command, homogeneous formations and uniform material which were lacking in the Allied force.

As regards the cavalry the Western Allies had six divisions, including one of three brigades. The enemy had at least nine, possibly more (one, the Guard Cavalry Division, of three brigades), as it is not clear from the German account how much cavalry was transferred from the Sixth Army to the Fourth Army.[2] It may be noted that a German cavalry division included, with its two or three cavalry brigades, horse artillery batteries and the two or three Jäger battalions, three or more machine-gun batteries and two or more companies of cyclists; and was thus, unlike ours, a force of all arms.

The German General Staff reveal nothing about the exact strength of the artillery. In a footnote it is mentioned that in addition to infantry divisions[Pg xvi] the III Reserve Corps contained siege artillery, Pionier formations and other technical troops; and in the text that ‘all the available heavy artillery of the Sixth Army to be brought up (to assist the Fourth Army) for the break-through.’ The Germans had trench-mortars (Minenwerfer) which are several times mentioned, whilst our first ones were still in the process of improvisation by the Engineers of the Indian Corps at Bethune.

The statement that ‘the enemy’s’ (i.e. British, French and Belgian) ‘superiority in material, in guns, trench-mortars, machine-guns and aeroplanes, etc., was two, three, even fourfold’ is palpably nonsense when said of 1914, though true perhaps in 1917 when the monograph was written.

The fact seems to be that the Germans cannot understand defeat in war except on the premise that the victor had superiority of numbers. To show to what extent this creed obtains: in the late Dr. Wylie’s Henry V., vol. II. page 216, will be found an account of a German theory, accepted by the well-known historian Delbrück, that the English won at Agincourt on account of superior numbers, although contemporary history is practically unanimous that the French were ten to one. Dr. Wylie sums it up thus:

‘Starting with the belief that the defeat of the French is inexplicable on the assumption that they greatly outnumbered the English, and finding that all contemporary authorities, both French and English, are agreed that they did, the writer builds up a theory that all the known facts can be explained on the supposition that the French were really much inferior to us in numbers ... and concludes that he cannot be far wrong if he puts the total number[Pg xvii] of French (the English being 6000) at something between 4000 and 7000.’

It may not be out of place to add that a German Staff Officer captured during the Ypres fighting said to his escort as he was being taken away: ‘Now I am out of it, do tell me where your reserves are concealed; in what woods are they?’ and he refused to believe that we had none. Apparently it was inconceivable to the German General Staff that we should stand to fight unless we had superior numbers; and these not being visible in the field, they must be hidden away somewhere.

Further light on what the Germans imagined is thrown by prisoners, who definitely stated that their main attack was made south of Ypres, because it was thought that our main reserves were near St. Jean, north-east of that town. From others it was gathered that what could be seen of our army in that quarter was in such small and scattered parties that it was taken to be an outpost line covering important concentrations, and the Germans did not press on, fearing a trap.

It is, however, possible that the German miscalculation of the number of formations engaged may not be altogether due to imaginary reserves, as regards the British Army. Before the war the Great General Staff knew very little about us. The collection of ‘intelligence’ with regard to the British Empire was dealt with by a Section known in the Moltkestrasse as the ‘Demi-monde Section,’ because it was responsible for so many countries; and this Section admittedly had little time to devote to us. Our organisation was[Pg xviii] different from that of any of the great European armies. Their field artillery brigades contained seventy-two guns, whereas ours had only eighteen guns or howitzers; their infantry brigades consisted of two regiments, each of three battalions, that is six battalions, not four as in the original British Expeditionary Force. To a German, therefore, an infantry brigade meant six battalions, not four, and if a prisoner said that he belonged to the Blankshire Regiment, the German might possibly believe he had identified three battalions, whereas only one would be present. This is actually brought out on page 118, when the author speaks of the 1st Battalion of the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment as the Königsregiment Liverpool, and indicates his ignorance of the British Army, when this single battalion engages the German Garde Regiment zu Fuss, by describing the fight not only as one of regiment against regiment, but as Garde gegen Garde (Guard against Guards).[3] Such is the fighting value of an English Line battalion. A victory over it is certainly claimed, but the significant sentence immediately follows: ‘any further advance on the 11th November by our Guard troops north of the road was now out of the question.’

It may be as well to point out that the ‘volunteers’ who it is said flocked to the barracks to form the Reserve Corps XXII to XXVII were not all volunteers in our sense of the word. The General Staff only[Pg xix] claims that 75 per cent. were untrained, a very different state of affairs from our New Armies, which had not 1 per cent. of trained soldiers. Many of the ‘volunteers’ were fully trained men liable to service, who merely anticipated their recall to the colours. It was well known before the war that in each army corps area Germany intended to form one ‘Active’ Corps and one or more ‘Reserve’ Corps. The original armies of invasion all contained Reserve Corps notably the IV Reserve of von Kluck’s Army, which marched and fought just as the active ones did. These first formed Reserve Corps were, it is believed, entirely made up of trained men, but those with the higher numbers XXII, XXIII, XXVI and XXVII, which appear in the Fourth Army, probably did contain a good percentage of men untrained before the war.

Ersatz divisions were formed of the balance of reservists after the Reserve divisions had been organised, and of untrained men liable for service. After a time the words ‘Active,’ ‘Reserve,’ and ‘Ersatz’ applied to formations lost their significance, as the same classes of men were to be found in all of them.

No attempt has been made to tone down the author’s patriotic sentiments and occasional lapses from good taste; the general nature of the narrative is too satisfactory to the British Army to make any omissions necessary when presenting it to the British public.

The footnotes deal with a number of the more important points raised, but are not exhaustive.

Note.—The German time, at the period of the year in question one hour earlier than ours, has been adhered to.The Notes of the Historical Section are distinguished from those of the Author by being printed in italics.In preparing the translation for issue it has not been thought necessary to supply all the maps provided in the original, as the general lie of the country must be fairly well known to British readers.

(Translation of Title Page)

Monographs on the Great War

THE BATTLE ON THE YSER AND OF

YPRES IN THE AUTUMN 1914

YPRES IN THE AUTUMN 1914

(DIE SCHLACHT AN DER YSER UND

BEI YPERN IM HERBST 1914)

BEI YPERN IM HERBST 1914)

FROM OFFICIAL SOURCES

PUBLISHED

BY ORDER OF THE GERMAN GENERAL STAFF

OLDENBURG, 1918, GERHARD STALLING

BY ORDER OF THE GERMAN GENERAL STAFF

OLDENBURG, 1918, GERHARD STALLING

PREFACE

By German Great Headquarters

The gigantic scale of the present war defies comparison with those of the past, and battles which formerly held the world in suspense are now almost forgotten. The German people have been kept informed of the progress of events on all fronts since the 4th August 1914, by the daily official reports of the German General Staff, but the general public will have been unable to gather from these a coherent and continuous story of the operations.

For this reason the General Staff of the German Field Army has decided to permit the publication of a series of monographs which will give the German people a general knowledge of the course of the most important operations in this colossal struggle of nations.

These monographs cannot be called histories of the war; years, even decades, must pass before all the true inwardness and connection of events will be completely revealed. This can only be done when the archives of our opponents have been opened to the world as well as our own and those of the General Staffs of our Allies. In the meantime the German[Pg xxiv] people will be given descriptions of the most important of the battles, written by men who took part in them, and have had the official records at their disposal.

It is possible that later research may make alterations here and there necessary, but this appears no reason for delaying publications based on official documents, indeed to do so would only serve to foster the legends and rumours which so easily take hold of the popular imagination and are so difficult, if not impossible, to correct afterwards.

This series of monographs is not therefore intended as an addition to military science, but has been written for all classes of the German public who have borne the burden of the war, and especially for those who have fought in the operations, in order to increase their knowledge of the great events for the success of which they have so gladly offered their lives.

GENERAL STAFF OF THE FIELD ARMY.

German Great Headquarters,

Autumn, 1917.

Autumn, 1917.

PRELIMINARY REMARKS

There is no more brilliant campaign in history than the advance of our armies against the Western Powers in August and early September 1914. The weak French attacks into Alsace, the short-lived effort to beat back the centre and right wing of our striking-force, the active defence of the Allied hostile armies and the passive resistance of the great Belgian and French fortresses, all failed to stop our triumphal march. The patriotic devotion and unexampled courage of each individual German soldier, combined with the able leading of his commanders, overcame all opposition and sent home the news of countless German victories. It was not long before the walls and hearts of Paris were trembling, and it seemed as if the conspiracy which half the world had been weaving against us for so many years was to be brought to a rapid conclusion. Then came the battle of the Marne, in the course of which the centre and right wings of the German Western Army were, it is true, withdrawn, but only to fight again as soon as possible, under more favourable strategic conditions. The enemy, not expecting our withdrawal, only followed slowly, and on 13th September[4] our troops brought him to a standstill along a line extending from the Swiss frontier to the Aisne, north-east of Compiègne. In the trench warfare[Pg 2] which now began our pursuers soon discovered that our strength had been by no means broken, or even materially weakened, by the hard fighting.

As early as 5th September, before the battle of the Marne, the Chief of the German General Staff had ordered the right wing should be reinforced by the newly-formed Seventh Army.[5] It soon became clear to the opposing commanders that any attempt to break through the new German front was doomed to failure, and that a decisive success could only be obtained by making an outflanking movement on a large scale against the German right wing. Thus began what our opponents have called the ‘Race to the Sea,’ in which each party tried to gain a decision by outflanking the other’s western wing. The good communications of France, especially in the north, enabled the Allied troops to be moved far more rapidly than our own, for the German General Staff had at their disposal only the few Franco-Belgian railways which had been repaired, and these were already overburdened with transport of material of every description. In spite of this, however, the French and British attacks failed to drive back the German right wing at any point. Not only did they find German troops ready to meet them in every case, but we were also generally able to keep the initiative in our hands.

In this manner by the end of September the opposing flanks had been extended to the district north of the Somme, about Péronne-Albert. A few days later began the interminable fighting round Arras and Lens,[Pg 3] and by the middle of October our advanced troops were near Lille, marching through the richest industrial country of France. The Army Cavalry was placed so as to threaten the hostile left flank, and to bring pressure against the communications with England. Our cavalry patrols pushed forward as far as Cassel and Hazebrouck, the pivots of the enemy’s movements, but they had to retire eastwards again when superior hostile forces moved up to the north-east. The reports which they brought back with them all pointed to preparations by the enemy for an attack on a large scale, and for another effort to turn the fortunes of the campaign to his favour. With this in view all available troops, including newly-arrived detachments from England, were to be used to break through the gap between Lille and Antwerp against our right wing, roll it up and begin the advance against the northern Rhine.

It must be remembered that at the time this plan was conceived the fortresses of Lille and Antwerp were still in French and Belgian possession. It was hoped that Lille, with its well-built fortifications, even though they were not quite up-to-date, would at least hold up the German right wing for a time. Antwerp was defended by the whole Belgian Army of from five to six divisions which were to be reinforced by British troops, and it was confidently expected that this garrison would be sufficiently strong to hold the most modern fortress in Western Europe against any attack, especially if, as was generally believed, this could only be carried out by comparatively weak forces. Thus it seemed that the area of concentration for the Franco-Belgian masses was secure until[Pg 4] all preparations were ready for the blow to be delivered through weakly-held Belgium against the rear of the German armies in the west. The plan was a bold one, but it was countered by a big attack of considerable German forces in the same neighbourhood and at the same time. The two opponents met and held each other up on the Yser and at Ypres, and here the last hope of our enemy to seize Belgium and gain possession of the rich provinces of Northern France before the end of the year was frustrated. The question arises how the Germans were able to find the men to do this, since it had been necessary to send considerable forces to the Eastern front to stop the Russian advance.

Whoever has lived through those great days of August 1914, and witnessed the wonderful enthusiasm of the German nation, will never forget that within a few days more than a million volunteers entered German barracks to prepare to fight the enemies who were hemming in Germany. Workmen, students, peasants, townspeople, teachers, traders, officials, high and low, all hastened to join the colours. There was such a constant stream of men that finally they had to be sent away, and put off till a later date, for there was neither equipment nor clothing left for them. By 16th August, before the advance in the west had begun, the Prussian War Minister in Berlin had ordered the formation of five new Reserve Corps to be numbered from XXII to XXVI, whilst Bavaria formed the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division, and Saxony and Würtemburg together brought the XXVII Reserve Corps into being. Old and young had taken up arms in August 1914, in their enthusiasm to defend their[Pg 5] country, and 75 per cent. of the new Corps consisted of these volunteers, the remainder being trained men of both categories of the Landwehrand the Landsturm, as well as some reservists from the depôts, who joined up in September. All these men, ranging from sixteen to fifty years of age, realised the seriousness of the moment, and the need of their country: they were anxious to become useful soldiers as quickly as possible to help in overthrowing our malicious enemies. Some regiments consisted entirely of students; whole classes of the higher educational schools came with their teachers and joined the same company or battery. Countless retired officers placed themselves at the disposal of the Government, and the country will never forget these patriots who took over commands in the new units, the formation of which was mainly due to their willing and unselfish work.

The transport of the XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXVI and XXVII Reserve Corps to the Western Front began on 10th October, and the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division followed shortly after. Only comparatively few experienced commanders were available for the units, and it was left to their keen and patriotic spirit to compensate as far as possible for what the men still lacked to play their part in the great struggle.

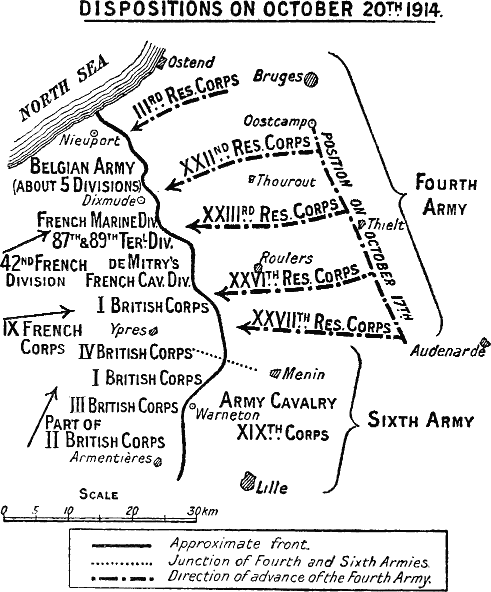

The situation of the armies on the Western Front at this time was as follows. In the neighbourhood of Lille the northern wing of the Sixth Army was fighting against an ever-increasing enemy. On 9th October, Antwerp, in spite of its strong fortifications and garrison, was taken after a twelve days’ siege directed by General von Beseler, commanding the III Reserve Corps, and well known in peace time as Chief of the[Pg 6] Engineer Corps and Inspector-General of Fortifications. The victorious besiegers had carried all before them. As they were numerically insufficient to invest Antwerp on the west, south and east, a break-through was attempted on a comparatively narrow front. It was completely successful, and Antwerp was occupied; but the main body of the Belgian army, in good fighting order, was able to escape westwards along the coast, to await the arrival of British and French reinforcements behind the Yser. Only about 5000 Belgians were taken prisoner, but some 20,000 Belgian and 2000 British troops[6] were forced into Holland. In consequence of this new situation, and of the reports of hostile concentrations in the area Calais-Dunkirk-Lille, the German General Staff decided to form a new Fourth Army under Duke Albert of Würtemburg. It was to be composed of the XXII, XXIII, XXVI, and XXVII Reserve Corps,[7] and was joined later on by the III Reserve Corps with the 4th Ersatz Division. By 13th October the detainment of this new Army was in full progress west and south-west of Brussels. On the evening of 14th October the four Reserve Corps began their march to the line Eecloo (fifteen miles east of Bruges)—Deynze—point four miles west of Audenarde.

In the meantime we had occupied the fortified town of Lille. It had been entered on 12th October by part of the XIX Saxon Corps and some Landwehr troops, after the town had suffered considerably owing to the useless efforts of French territorial troops to[Pg 7] defend it. The order to the garrison was: ‘The town is to be held till the Tenth French Army arrives’; it resulted in the capture of 4500 French prisoners, who were sent to Germany. On the 14th the right wing of the Sixth Army, consisting of the XIII Würtemburg and XIX Saxon Corps, pushed forward to the Lys, behind a screen of three Cavalry Corps.[8] They took up a position covering Lille, from Menin through Comines to Warneton and thence east of Armentières, where they came into touch with the 14th Infantry Division which was further south near the western forts of Lille. To the north of the Sixth Army, the III Reserve Corps, with its three divisions from Antwerp, was advancing westwards on a broad front. By the 14th it had driven back the hostile rearguards and reached a line from Bruges to near Ghent. Airmen and reconnaissance detachments had recognised movements of large bodies of troops about Hazebrouck, Lillers and St. Omer and reported disembarkations on a big scale at Dunkirk and Calais. In addition to this, considerable hostile forces had reached Ypres, and appeared to be facing more or less southwards opposite the northern wing of the Sixth Army.[9]

An order issued on 14th October, by the Chief of the German General Staff, gave the following instructions for the German forces between Lille and the sea. The Sixth Army was at first to remain entirely on the defensive along the line Menin-Armentières-La Bassée[Pg 8] and to await the attack of our new Fourth Army against the left flank of the enemy. The offensive action of the Fourth Army after its deployment was to be so directed that the III Reserve Corps, which now belonged to it, should move as its right wing in echelon along the coast, whilst its left was to advance through Menin.

In accordance with these orders the III Reserve Corps occupied Ostend on the 15th, its left wing reaching the line of the Thourout-Roulers road. The Corps was then ordered not to advance further for a few days, so as to avoid the attention of the British and French, who were advancing against the north wing of the Sixth Army, being drawn prematurely to movements in this neighbourhood. Only patrols therefore were sent out to reconnoitre across the Yser and the canal south of it. On the 17th the XXII, XXIII, XXVI and XXVII Reserve Corps reached the line Oostcamp (south of Bruges)-Thielt—point six miles east of Courtrai. On the advance of these four new Corps, the III Reserve Corps was to draw away to the right wing, and during the 17th and the following morning it moved up to the sector of attack allotted to it immediately south of the coast, and cleared the front of the Fourth Army. The reconnaissance activity of the previous days had in places led to severe fighting, especially on the southern wing in front of the 6th Reserve Division. It was found that the Belgian rearguards still held part of the ground east of the Yser and of the canal to Ypres. Any attempt to advance beyond this water-barrier was out of the question, as the bridges had been blown up and the whole line put in a state of defence.

The screening of the advancing Fourth Army by the III Reserve Corps was a brilliant success. At midday on the 18th, Field-Marshal French, who was to direct the enemy’s attack from the line of the Yser, was still in ignorance of our new Army. He believed he had time to prepare for his attack, and his only immediate care was to secure the line from Armentières to the sea for the deployment. After the events on the Marne, Field-Marshal French had particularly requested General Joffre, the Allied commander,[10] that he might be placed on the northern flank of the line. He would then be close to Calais, which had already become an English town,[11] he would be able to protect the communications to his country; and, further, the fame to be gained by a decisive and final victory attracted this ambitious commander to the north. As a result the II British Corps under General Smith-Dorrien was now in action against the strong German positions between Vermelles (four miles south-west of La Bassée) and Laventie (west of Lille).[12] Further to the north the III British Corps was fighting against the Saxons advancing from Lille and our I, II and IV Cavalry Corps.[13] The I British Cavalry Corps was covering the[Pg 10] hostile advance on the line Messines-Gheluvelt, south-east of Ypres.[14] Immediately to the north again, the newly formed IV British Corps, consisting of the 7th Infantry Division and 3rd Cavalry Division, had arrived in the area Gheluvelt-Zonnebeke, pursued in its retreat by von Beseler’s columns (III Reserve Corps). On its left the I British Corps had marched up to Bixschoote,[15] and the gap between this place and Dixmude had been closed by a French Cavalry Division which connected up with the Belgian Army. The last, reinforced by two French Territorial divisions, was engaged in preparing the line of the Yser up to the sea for the most stubborn defence. These strong forces were to cover the arrival of the VIII and X French Corps[16] and were to deliver the first blow against our supposed right wing.

On the 18th one of our cyclist patrols which had gone out far in advance of its Corps was surrounded near Roulers, and it was only by its capture that the enemy definitely discovered the arrival of the new German Corps, whose formation, however, had not been unknown to him, thanks to his good Secret Service system. Field-Marshal French was now confronted with a new situation. The preparations for his big attack were not yet completed. The superiority of the masses already concentrated did not yet appear to him to be suffi[Pg 11]cient to guarantee success against the enemy’s advance. The British commander therefore decided to remain on the defensive[17] against our new Fourth Army, until the completion of the French concentration. His line was already closed up to the sea, it was naturally strong, and fresh troops were arriving daily. The danger threatening Dunkirk and Calais had the effect of making England put forth her full energy; the British troops fought desperately to defend every inch of ground, using every possible means to keep up the sinking spirits of the Belgians. They demanded and received rapid assistance from the French, and were backed up by fresh reinforcements from England.

From the German point of view the patriotic enthusiasm and unconditional determination to win the war which pervaded the new Fourth Army gave every prospect of successfully closing with the enemy, who was apparently still engaged in concentrating and reorganising his forces, and gaining Calais, the aim and object of the 1914 campaign.

Our offensive, however, struck against a powerful army, fully deployed and ready to meet us. The British boast that they held up our attack with a great inferiority of numbers, but this was only true in the case of the 7th Division during the first two days in the small sector Zonnebeke-Gheluvelt. On 22nd October between Armentières and the sea there were eight Corps opposed to the seven attacking German Corps; and, besides, the enemy had prepared a series of lines of strong trenches covered by[Pg 12] an extensive system of artificial obstacles. In the course of the operations that developed, the relative strength of the opposing forces never appreciably altered in our favour.[18] The moral strength of our troops made up for the numerical superiority of the enemy. Our attack drove the hostile lines well back and destroyed, it is hoped for ever, the ambition of our opponent to regain Belgium by force of arms.

The great desire of the Germans to defeat the hostile northern wing, and to hit hardest the most hated of all our enemies, and, on the other side, the obstinate determination of the British to hold on to the passages to their country, and to carry out the offensive to the Rhine with all their resources, resulted in this battle being one of the most severe of the whole war. The deeds of our troops, old and young, in the battle on the Yser and of Ypres can never be sufficiently praised, and in spite of great losses their enthusiasm remained unchecked and their offensive spirit unbroken.

THE THEATRE OF OPERATIONS

The country in which it was hoped to bring about the final decision of the campaign of 1914 was not favourable to an attack from east to west.

Western Flanders, the most western part of Belgium, is almost completely flat, and lies only slightly above sea-level, and in some parts is even below it. Mount Kemmel, in the south, is the only exception; rising to a height of over 500 feet, it is the watch-tower of Western Flanders. Before the war it was a well-wooded ridge with pretty enclosures and villages. From its slopes and summits could be seen the whole countryside from Lille to Menin and Dixmude.

The possession of this hill was of great importance. Our cavalry actually occupied it during the early days of October, but when the enemy advanced he immediately attacked it. The XIX Saxon Corps was still too far away to help, and so Mount Kemmel fell into the enemy’s hands. During the battle of Ypres it was his best observation post, and of the utmost assistance to his artillery.

We repeatedly succeeded in gaining a footing on the eastern crest of the ridge in front of Ypres, but in the autumn of 1914, as also later in the war, this was always the signal for the most desperate fighting.[Pg 14] It was thus that the heights of St. Eloi,[19] the high-lying buildings of Hooge and the village of Wytschaete won their sanguinary fame.

Lying in the midst of luxuriant meadows, with its high ramparts and fine buildings, Ypres was formerly one of the most picturesque towns in Flanders. In the fourteenth century it had a considerable importance, and became the centre of the cloth-weaving trade on its introduction from Italy. Bruges, lying close to the coast, became the market for its wares. The Clothweavers’ Guild, which accumulated great wealth, erected in Ypres a fine Gothic hall, whose towers with those of St. Martin’s Church were landmarks for miles round. In modern times, however, the importance of the town greatly diminished. The cloth-weaving industry drifted away to the factories of Menin and Courtrai; and Ypres, like its dead neighbour Bruges, remained only a half-forgotten memory of its former brilliance.

The war has brought fresh importance to the town, but of a mournful kind. On the impact of the German and Anglo-French masses in Flanders in the autumn of 1914, it became the central pivot of the operations. The enemy dug his heels into the high ground in front of it; for, as an Englishman has written, it had become a point of honour to hold the town. Ypres lay so close to the front that our advance could be seen from its towers, and the enemy was able to use it for concealing his batteries and sheltering his reserves. For the sake of our troops we had to bring it under fire;[Pg 15] for German life is more precious than the finest Gothic architecture. Thus the mythical death of Ypres became a reality: no tower now sends forth its light across the countryside, and a wilderness of wrecked and burnt-out houses replaces the pretty town so full of legend and tradition in the history of Flanders.

The streams which run northwards from the hills about Ypres unite for the most part near the town and flow into the Yser canal, which connects the Lys at Comines with the sea at Nieuport. This canal passes through the Ypres ridge near Hollebeke and, following northwards the course of a small canalised tributary of the Yser, meets the Yser itself south of Dixmude. The dunes at Nieuport have been cut through by engineers for its exit to the sea. It is only from Dixmude northwards that the canal becomes an obstacle which requires proper bridging equipment for its passage. Its high embankments to the south of Dixmude, however, give excellent cover in the otherwise flat country and greatly simplify the task of the defender.

The canal acquired a decisive importance when the hard-pressed Belgians, during the battle on the night of 29th-30th October, let in the sea at flood-tide through the sluices into the canal, and then by blowing up the sluice-gates at Nieuport, allowed it to flood the battlefield along the lower Yser. By this means they succeeded in placing broad stretches of country under water, so much so that any extensive military operations in that district became out of the question. The high water-level greatly influenced all movements over a very large area. By his order the King of the Belgians destroyed for years the natural[Pg 16] wealth of a considerable part of his fertile country, for the sea-water must have ruined all vegetation down to its very roots.

The country on both sides of the canal is flat, and difficult for observation purposes. The high level of the water necessitates drainage of the meadows, which for this purpose are intersected by deep dykes which have muddy bottoms. The banks of the dykes are bordered with willows, and thick-set hedges form the boundaries of the cultivated areas. Generally speaking, the villages do not consist of groups of houses: the farms are dispersed either singly, or in rows forming a single street. The country is densely populated and is consequently well provided with roads. But these are only good where they have been made on embankments and are paved. The frequent rains, which begin towards the end of October, rapidly turn the other roads into mere mud tracks and in many cases make them quite useless for long columns of traffic.

The digging of trenches was greatly complicated by rain and surface-water. The loam soil was on the whole easy to work in; but it was only on the high ground that trenches could be dug deep enough to give sufficient cover against the enemy’s artillery fire; on the flat, low-lying ground they could not in many cases be made more than two feet deep.

A few miles south of the coast the country assumes quite another character: there are no more hedges and canals: instead gently rolling sand-hills separate the land from the sea, and this deposited sand is not fertile like the plains south of them. A belt of dunes prevents the sea encroaching on the land.

The greatest trouble of the attacker in all parts of Flanders is the difficulty of observation. The enemy, fighting in his own country,[20] had every advantage, while our artillery observation posts were only found with the utmost trouble. Our fire had to be directed from the front line, and it frequently happened that our brave artillerymen had to bring up their guns into the front infantry lines in order to use them effectively. Although the enemy was able to range extremely accurately on our guns which were thus quickly disclosed, nothing could prevent the German gunners from following the attacking infantry.

Observation from aeroplanes was made very difficult by the many hedges and villages, so that it took a long time to discover the enemy’s dispositions and give our artillery good targets.

Finally, the flat nature of the country and the consequent limitations of view were all to the advantage of the defenders, who were everywhere able to surprise the attackers. Our troops were always finding fresh defensive lines in front of them without knowing whether they were occupied or not. The British, many of whom had fought in a colonial war against the most cunning of enemies in equally difficult country, allowed the attacker to come to close quarters and then opened a devastating fire at point-blank range from rifles and machine-guns concealed in houses and trees.

In many cases the hedges and dykes split up the German attacks so that even the biggest operations degenerated into disconnected actions which made the[Pg 18] greatest demands on the powers of endurance and individual skill of our volunteers. In spite of all these difficulties our men, both old and young, even when left to act on their own initiative, showed a spirit of heroism and self-sacrifice which makes the battle on the Yser a sacred memory both for the Army and the Nation, and every one who took part in it may say with pride, ‘I was there.’

THE ADVANCE OF THE FOURTH ARMY

An Army Order of 16th October 1914 gave the following instructions for the 18th:—

The III Reserve Corps to march to the line Coxyde-Furnes-Oeren, west of the Yser.The XXII Reserve Corps to the line Aertrycke-Thourout.The XXIII Reserve Corps to the line Lichtervelde-Ardoye.The XXVI Reserve Corps to the Area Emelghem-Iseghem, and, on the left wing, the XXVII Reserve Corps to the line Lendelede-Courtrai.

The XXII, XXIII, XXVI and XXVII Reserve Corps all reached their appointed destinations on the evening of the 18th without meeting any strong resistance. Along almost the whole front our advanced guards and patrols came into touch with weak hostile detachments who were awaiting our advance well entrenched, and surprised us with infantry and artillery fire. At Roulers a hot skirmish took place. Aeroplanes circling round, motor-lorries bustling about, and cavalry patrols pushing well forward showed that the British now realised the strength of the new German forces.

On 20th October none of the I British Corps were on the right of the IV Corps; the map should read British Cavalry Corps. It is also inaccurate to represent the whole III British Corps as north of Armentières—only one of its Divisions was—while the II Corps was certainly too closely pressed to detach any troops to the north as depicted in the diagram.

In the meantime, on the extreme right wing of the[Pg 20]

[Pg 21] Army, the troops of General von Beseler had opened the battle on the Yser. During its advance northwards to cross the Yser at the appointed places the III Reserve Corps had encountered strong opposition east of the river-barrier. The men knew they were on the decisive wing of the attack, and they pushed ahead everywhere regardless of loss. In a rapid assault the 4th Ersatz Division captured Westende from the Belgians, although a gallant defence was put up, and in spite of the fact that British torpedo-boats and cruisers took part in the action from the sea with their heavy artillery[21] both during the advance and the fight for the town. Further south the 5th Reserve Division deployed to attack a strongly entrenched hostile position. The 3rd Reserve Jäger Battalion captured the obstinately defended village of St. Pierre Cappelle after severe hand-to-hand fighting, whilst the main body of the division succeeded in pushing forward to the neighbourhood of Schoore. The 6th Reserve Division, commanded by General von Neudorff, also closed with the enemy. It captured Leke, and Keyem, defended by the 4th Belgian Division; but even this Brandenburg Division, for all its war experience, found the task of forcing the crossings over the Yser too much for it.

[Pg 21] Army, the troops of General von Beseler had opened the battle on the Yser. During its advance northwards to cross the Yser at the appointed places the III Reserve Corps had encountered strong opposition east of the river-barrier. The men knew they were on the decisive wing of the attack, and they pushed ahead everywhere regardless of loss. In a rapid assault the 4th Ersatz Division captured Westende from the Belgians, although a gallant defence was put up, and in spite of the fact that British torpedo-boats and cruisers took part in the action from the sea with their heavy artillery[21] both during the advance and the fight for the town. Further south the 5th Reserve Division deployed to attack a strongly entrenched hostile position. The 3rd Reserve Jäger Battalion captured the obstinately defended village of St. Pierre Cappelle after severe hand-to-hand fighting, whilst the main body of the division succeeded in pushing forward to the neighbourhood of Schoore. The 6th Reserve Division, commanded by General von Neudorff, also closed with the enemy. It captured Leke, and Keyem, defended by the 4th Belgian Division; but even this Brandenburg Division, for all its war experience, found the task of forcing the crossings over the Yser too much for it.

The fighting on 18th October resulted in bringing us a thousand or two thousand yards nearer the Yser, but it had shown that the fight for the river line was to be a severe one. The Belgians seemed determined to sell the last acres of their kingdom only at the highest possible price. Four lines of trenches had been dug, and it could be seen that every modern[Pg 22] scientific resource had been employed in putting the villages on the eastern bank of the river into a state of defence. A great number of guns, very skilfully placed and concealed, shelled the ground for a considerable distance east of the river, and in addition to this our right flank was enfiladed by the heavy naval guns from the sea. Battleships, cruisers and torpedo-boats worried the rear and flank of the 4thErsatz Division with their fire, and the British had even brought heavy artillery on flat-bottomed boats close inshore.[22] They used a great quantity of ammunition, but the effect of it all was only slight, for the fire of the naval guns was much dispersed and indicated bad observation. It became still more erratic when our long-range guns were brought into action against the British Fleet. Detachments of the 4th Ersatz Division had to be echeloned back as far as Ostend, in order to defend the coast against hostile landings. During the day the General Commanding the III Reserve Corps decided not to allow the 4th Ersatz Division to cross the Yser at Nieuport, on account of the heavy fire from the British naval guns, but to make it pass with the main body of the Corps behind the 5th Reserve Division in whose area the fight appeared to be progressing favourably. The Ersatz Division was informed accordingly. On the 19th another effort would have to be made to force the crossings of the river by frontal attack, for everywhere to the south strong opposition had been encountered. From near Dixmude French troops carried on the line of the compact Belgian Army. It was[Pg 23] against these that the new Reserve Corps were now advancing.

On the night of the 18th and morning of the 19th October a strong attack was delivered from the west by the 4th Belgian Division, and from the south-west by a brigade of the 5th Belgian Division and a brigade of French Marine Fusiliers under Admiral Ronarch, against Keyem, held by part of the 6th Reserve Division. They were driven back after heavy fighting. During the 19th the southern wing of the Brandenburg (III) Reserve Corps succeeded in advancing nearer the river and, on its left, part of the artillery of the XXII Reserve Corps came into action in support of it, thereby partly relieving the III Reserve Corps, which until that day had been fighting unassisted.

On the 19th more or less heavy fighting developed on the whole front of the Fourth Army. The XXII Reserve Corps advanced on Beerst and Dixmude and fought its way up into line with the III Reserve Corps. In front of it lay the strong bridge-head of Dixmude, well provided with heavy guns. The whole XXIII Reserve Corps had to be deployed into battle-formation, as every locality was obstinately defended by the enemy. In the advance of the 45th Reserve Division the 209th Reserve Regiment late in the evening took Handzaeme after severe street fighting, and the 212th Reserve Regiment took the village of Gits, whilst Cortemarck was evacuated by the enemy during the attack. The 46th Reserve Division in a running fight crossed the main road toThourout, north of Roulers, and by the evening had arrived close to Staden. Heavy street fighting in the latter place continued during the night: the[Pg 24] enemy, supported by the population, offered strong resistance in every house, so that isolated actions continued behind our front lines, endangering the cohesion of the attacking troops, but never to a serious extent.

The XXVI Reserve Corps encountered strong opposition at Rumbeke, south-east of Roulers; but all the enemy’s efforts were in vain, and the 233rd Reserve Infantry Regiment, under the eyes of its Corps Commander, General von Hügel, forced its way through the rows of houses, many of which were defended with light artillery and machine-guns. A very heavy fight took place for the possession of Roulers, which was stubbornly defended by the French; barricades were put up across the streets, machine-guns fired from holes in the roofs and windows, and concealed mines exploded among the advancing troops. In spite of all this, by 5 P.M. Roulers was taken by the 233rd, 234th and 235th Reserve Infantry Regiments, attacking from north, east and south respectively. Further to the south, after a small skirmish with British cavalry, the 52nd Reserve Division reached Morslede, its objective for the day. On its left again, the XXVII Reserve Corps had come into contact with the 3rd British Cavalry Division which tried to hold up the Corps in an advanced position at Rolleghem-Cappelle. After a lively encounter the British cavalry was thrown back on to the 7th British Division, which held a strong position about Dadizeele.[23]

Thus by the evening of 19th October the situation had been considerably cleared up, in so far as we now knew that the Belgians, French and British not only held the Yser and the Ypres canal, but also the high ground east and north-east of Ypres. Everything pointed to the fact that an unexpectedly strong opponent was awaiting us in this difficult country, and that a very arduous task confronted the comparatively untrained troops of Duke Albert of Würtemburg’s Army. In the meantime the Commander of the Sixth Army, Crown Prince Rupert of Bavaria, after a discussion at Army Headquarters with General von Falkenhayn, Chief of the General Staff, decided to renew the attack, as the left wing of the Fourth Army had now come up on his immediate right. In consequence of this decision, the XIII Corps was moved from its position on the line Menin-Warneton and replaced by three Cavalry Divisions of the IV Cavalry Corps. There can be no doubt that the attacks of the Sixth Army, which began on the 20th and were continued with frequent reinforcements of fresh troops, had the effect of holding the enemy and drawing a strong force to meet them. They were not, however, destined to have any decisive success, for the offensive strength of the Sixth Army had been reduced by previous fighting, and it was not sufficient to break through the enemy’s strongly entrenched positions.[24] All the more therefore were the hopes of Germany centred in the Fourth Army, which was fighting further northwards, for in its hands lay the fate of the campaign in Western Europe at this period.

THE OPERATIONS OF THE FOURTH ARMY FROM 20th OCTOBER TO 31st OCTOBER 1914

On 20th October the battle broke out along the whole line, on a front of about sixty miles. The enemy had got into position, and was prepared to meet the attack of Duke Albert of Würtemburg’s Army. On the very day that the British, French and Belgians intended to begin their advance they found themselves compelled to exert all their strength to maintain their positions against our offensive. The British and French had to bring up constant reinforcements, and a hard and bitter struggle began for every yard of ground. The spirit in which our opponents were fighting is reflected in an order of the 4th Belgian Division, picked up in Pervyse on 16th October. This ran: ‘The fate of the whole campaign probably depends on our resistance. I (General Michel) implore officers and men, notwithstanding what efforts they may be called upon to make, to do even more than their mere duty. The salvation of the country and therefore of each individual among us depends on it. Let us then resist to our utmost.’

We shall see how far the soldiers of the Fourth Army, opposed to such a determined and numerically superior enemy, were able to justify the confidence which had been placed in them, a confidence expressed in the following proclamations by their highest commanders on their arrival in Belgium:

Great Headquarters,

14th October 1914.To the Fourth Army,—I offer my welcome to the Fourth Army, and especially to its newly-formed Reserve Corps, and I am confident that these troops will act with the same devotion and bravery as the rest of the German Army.Advance, with the help of God—my watchword.(Signed) William, I. R.ARMY ORDER.

I am pleased to take over the command of the Army entrusted to me by the Emperor. I am fully confident that the Corps which have been called upon to bring about the final decision in this theatre of war will do their duty to their last breath with the old German spirit of courage and trust, and that every officer and every man is ready to give his last drop of blood for the just and sacred cause of our Fatherland. With God’s assistance victory will then crown our efforts.Up and at the enemy. Hurrah for the Emperor.(Signed) Duke Albert of Würtemburg,

General and Army Commander.Army Headquarters, Brussels,

15th October 1914.

Who can deny that the task set to the Fourth Army was not an infinitely difficult one. It would have probably been achieved nevertheless if the Belgians at the moment of their greatest peril had not called the sea to their aid to bring the German attack to a halt. Let us, however, now get down to the facts.

On 20th October the III Reserve Corps, the battering ram of the Fourth Army, began an attack with its 5th Reserve Division, supported by almost the whole of the Corps artillery, against the sector of the Yser west of the line Mannekensvere-Schoor[Pg 28]bakke. The 4th Ersatz Division to the north and the 6th Reserve Division to the south co-operated. By the early hours of the 22nd, the 5th and 6th Reserve Divisions had driven the enemy back across the river in spite of the support given him by British and French heavy batteries.[25] In front of the 4th Ersatz Division the enemy still held a bridge-head at Lombartzyde. At 8.15 A.M. on the 22nd the glad tidings reached the Staff of the 6th Reserve Division, that part of the 26th Reserve Infantry Regiment had crossed the Yser. Under cover of darkness the 1st and 2nd Battalions of this regiment had worked their way up to the north-eastern part of the bend of the Yser, south of Schoore, and had got into the enemy’s outposts on the eastern bank with the bayonet. Not a shot had been fired, and not an unnecessary noise had disturbed the quiet of the dawning day. Volunteers from the engineers silently and rapidly laid bridging material over the canal. In addition an old footbridge west of Keyem, which had been blown up and lay in the water, was very quickly made serviceable again with some planks and baulks. The Belgians had considered their position sufficiently protected by the river, and by the outposts along the eastern bank. By 6 A.M. German patrols were on the far side of the Yser, and the enemy’s infantry and machine-gun fire began only when they started to make a further advance. Three companies of the 1st and two companies of the 2nd Battalion, however, as well as part of the 24th Reserve Infantry Regiment, had already crossed the temporary bridges at the double and taken[Pg 29] up a position on the western bank: so that, in all, 2½ battalions and a machine-gun company were now on the western bank.

The enemy realised the seriousness of the situation, and prepared a thoroughly unpleasant day for those who had crossed. Heavy and light guns of the British and French artillery[26]hammered incessantly against the narrow German bridge-head and the bridges to it. Lying without cover in the swampy meadows the infantry was exposed beyond all help to the enemy’s rifle and machine-gun fire from west and south-west. The small force repulsed counter-attacks again and again, but to attempt sending reinforcements across to it was hopeless. Some gallant gunners, however, who had brought their guns close up to the eastern bank, were able to give great help to their friends in their critical situation. Thus assisted the infantry succeeded in holding the position, and during the following night was able to make it sufficiently strong to afford very small prospect of success to any further hostile efforts. During the night several Belgian attacks with strong forces were repulsed with heavy loss, and the 6th Reserve Division was able to put a further 2½ battalions across to the western bank of the Yser bend. On the 23rd we gained possession of Tervaete, and the dangerous enfilade fire on our new positions was thereby considerably diminished. Dawn on 24th October saw all the infantry of the 6th Reserve Division west of the river. A pontoon bridge was thrown across the north-eastern part of the Yser bend, but it was still impossible to bring guns forward on account[Pg 30] of the enemy’s heavy artillery fire. The 5th Reserve Division still lay in its battle positions along the river bank north of Schoorbakke, but every time attempts were made to cross the French and Belgian artillery smashed the bridges to pieces. The 4th Ersatz Division suffered heavily, as it was subjected to constant artillery fire from three sides, and to entrench was hopeless on account of the shifting sands and the high level of the ground water. Whenever fire ceased during the night strong hostile attacks soon followed; but they were all repulsed. The withdrawal of the main body of theErsatz Division behind the 6th Reserve Division to cross the Yser, as General von Beseler had once planned, had become impracticable for the moment, for it had been discovered through the statements of prisoners that the 42nd French Division had arrived in Nieuport to assist the Belgians. The 4th Ersatz Division, which had been weakened on the 18th by the transfer of one of its three brigades to the 5th Reserve Division, could not be expected to bring the new enemy to his knees by the running fight that it had been hitherto conducting. The canal alone was sufficient obstacle to make this impracticable; in addition, the fire of the enemy’s naval guns from the sea prevented any large offensive operations in the area in question. Thus the Ersatz troops were compelled to resign themselves to the weary task of maintaining their positions under the cross-fire of guns of every calibre, to driving back the hostile attacks, and to holding the Belgian and French forces off in front of them by continually threatening to take the offensive. It was not until some long-range batteries were placed at the disposal of the division that its[Pg 31] position improved. A couple of direct hits on the enemy’s ships soon taught them that they could no longer carry on their good work undisturbed. Their activity at once noticeably decreased, and the more the German coast-guns gave tongue seawards from the dunes, the further the ships moved away from the coast and the less were they seen.

General von Beseler never for a moment doubted that the decision lay with the 5th and 6th Reserve Divisions, especially as the four Corps of the Fourth Army, fighting further south, had not yet been able to reach the canal-barrier with any considerable forces.

The XXII Reserve Corps, commanded by General of Cavalry von Falkenhayn, had in the meantime come into line south of General von Beseler’s troops, and had already fought some successful actions. It had arrived on the 19th in the district east of Beerst and about Vladsloo, just in time to help in driving back the Franco-Belgian attack against the southern flank of the 6th Reserve Division.[27] That same evening it was ordered to attack from north and south against the Dixmude bridge-head, an exceptionally difficult task. In addition to the fact that the swampy meadows of the Yser canal limited freedom of movement to an enormous extent, the Handzaeme canal, running at right angles to it from east to west, formed a most difficult obstacle. Dixmude lay at the junction of these two waterways, and behind its bridge-head lines were the Belgian ‘Iron’ Brigade under Colonel Meiser, the French Marine Fusilier Brigade under Admiral Ronarch, and part of the 5th Belgian Division, determined to defend[Pg 32] the place at all costs. About eighty guns of every calibre commanded with frontal and enfilade fire the ground over which Falkenhayn’s Corps would have to attack. On the 20th, in spite of all these difficulties, the 44th Reserve Division, on the northern wing of the Corps, captured Beerst and reached the canal bank west of Kasteelhoek in touch with von Beseler’s Corps. The 43rd Reserve Division, advancing on the left wing, took Vladsloo and several villages south-east of it on the northern bank of the Handzaeme Canal. By the light of the conflagration of those villages the reach of the canal between Eessen and Zarren was crossed on hastily constructed footbridges, and a further advance made in a south-westerly direction. Eessen itself was occupied, and the attack brought us to within a hundred yards of the enemy. He realised his extremely critical situation,[28] and his cyclists and all possible reserves at hand were put in to the fight. Owing to the severe hostile artillery fire the German losses were by no means slight. On one occasion when our advancing infantry units were losing touch with one another in this difficult country, a big hostile counter-attack was delivered from Dixmude. After a heavy struggle the onrush of the enemy was held up, mainly owing to our artillery, which heroically brought its guns up into position immediately behind the infantry front line.

During the night the 43rd Reserve Division reorganised in order to recommence its attack on the bridge-head from east and south-east on the following morning. Days of terrific fighting ensued. The garrison of the bridge-head had received orders to[Pg 33] hold out to the last man, and had been informed that any one who attempted to desert would be shot without mercy by men placed for this purpose to guard all the exits from the town. The Belgians were indeed fighting for their very existence as a nation. Nevertheless by the 21st October the 43rd Reserve Division, which consisted of volunteers from the Guard Corps Reservists, had taken the château south of Dixmude, and Woumen. The opposing sides lay within a hundred yards of each other. Artillery preparation, attack and counter-attack went on incessantly. Our artillery did fearful havoc and Dixmude was in flames. The Franco-Belgian garrison was, however, constantly reinforced, and conducted itself most gallantly. From the north the battalions of the 44th Reserve Division were able to advance slightly and drive the enemy back on to the town, and German batteries were brought up into, and at times even in front of, the infantry front line. Although we were unable to force our way into Dixmude, on the evening of the 23rd our troops were in position all round it.

On the left of the XXII Reserve Corps, the XXIII Reserve Corps, under General of Cavalry von Kleist, had advanced at 9 A.M. on 20th October on the front Handzaeme-Staden in order to reach the canal on the line Noordschoote-Bixschoote. The 45th Reserve Division was on the right and the 46th Reserve Division on the left. After some hours of street fighting Staden was finally surrounded and taken by the 46th Reserve Division. By nightfall a line from Clercken to the eastern edge of Houthulst Forest was reached. On the 21st the Corps had to cross a stretch of country which put these partially trained troops and their[Pg 34] inexperienced officers to a very severe test. The great forest of Houthulst with its dense undergrowth made it exceedingly difficult to keep direction in the attack and to maintain communication between units fighting an invisible opponent. Small swampy streams such as the Steenebeck offered favourable opportunities to the enemy to put up a strong defence behind a succession of depressions. Thus our gallant troops after every successful assault found themselves confronted by another strong position: but unwavering and regardless of loss, they continued their advance.

By the evening of the 21st the 46th Reserve Division had completely driven the enemy out of Houthulst Forest,[29] whilst its sister-division had advanced north of the Steenebeck, and with its northern wing supporting the Corps fighting immediately north of it, had pushed forward to beyond Woumen. On the morning of the 22nd the heavy artillery opened fire against the French positions on the Yser canal to prepare the break-through. Unfortunately however only the northern Division was able to reach the sector allotted to the Corps, and an Army Order directed the 46th Reserve Division to the south-west against the line Bixschoote-Langemarck, in order to help carry for[Pg 35]ward the attack of the XXVI Reserve Corps, which was completely held up in front of the latter place. As a result of this the advance of von Kleist’s Corps also came to a standstill, although it had achieved considerable fame during the day. In spite of a desperate resistance the 210th Reserve Regiment stormed the strongly entrenched village of Merckem and the village of Luyghem lying north of it; a daring attack by the 209th and 212th Reserve Regiments broke through the enemy’s positions on the Murtje Vaart, whilst the 46th Reserve Division attempted to overrun the Kortebeck sector, supported by the concentrated fire of its artillery in position along the south-western edge of Houthulst Forest. The 216th Reserve Regiment took Mangelaere by storm, in doing which its gallant commander, Colonel von Grothe, was killed at the head of his troops. The 1st British Division held a strong position along the Kortebeck, in touch with the French, and artillery of every calibre near Noordschoote enfiladed the German attack.[30]The British themselves speak of our attack as a magni[Pg 36]ficent feat of arms carried out with infinite courage and brilliant discipline. The men sang songs as they charged through a hail of bullets in closed ranks up to the enemy’s defences. The 212th Reserve Regiment under Colonel Basedow, reinforced and carried forward by fresh detachments of the 209th Reserve Regiment, pushed its way into the strongly fortified village of Bixschoote. The enemy on our side of the canal, on the line Bixschoote-Langemarck-Zonnebeke, was threatened with annihilation. Bixschootecommanded the main road and the canal-crossing to Poperinghe, where the enemy was detraining his reinforcements.[31] The British therefore fought with the courage of desperation: for not only was the fate of the high ground east and north-east of Ypres now in the balance, but also the chance of being able to carry out the great Anglo-French offensive which had been planned.Ypres and the high ground east of the canal were on no account to be lost, and furious counter-attacks were therefore delivered against the intermingled German units. Nevertheless our gallant volunteers pressed on, using their bayonets and the butts of their rifles, until the furious hand-to-hand fighting was finally decided in our favour. At 6.30 that evening Bixschoote was ours. Unfortunately, however, owing to an order being misunderstood, it was lost again during the night: the exhausted attacking troops were to be relieved under cover of darkness, but they assembled and marched back before the relieving force had arrived. The enemy, ever watchful, immediately advanced into the evacuated village and[Pg 37] took position among the ruins. Simultaneously a big hostile counter-attack drove the 46th Reserve Division from the high ground south of Kortebeck, which it had captured, and pressed it back beyond the stream again. The spirit and strength of the young and inexperienced troops seemed to be broken, and only a few of the subordinate commanders had yet learnt how to deal with critical situations. Officers of the General Staff and Divisional Staffs had to help to reorganise the men; they immediately turned and followed their new leaders, and were taken forward again to the attack. Thus on the 23rd the high ground south of the Kortebeck was won back by the 46th Reserve Division, but Bixschoote remained lost to us, and Langemarck could not be captured.[32]

On 22nd October, for the first time, our attack was directed from the north against Ypres. If the British and French did not intend to give up their offensive plans, and thereby their last hope of retaking Belgium and the wealthy provinces of Northern France from the hated German, they would have to maintain their positions along the Ypres bridge-head east of the canal betweenComines and the coast. For this reason the country round Ypres was the central area of the Anglo-French defence from the beginning to the end of the battle. Our opponents defended this position on a wide semicircle by successive lines of trenches and with their best troops. Every wood, every village, every farm and even every large copse has won for itself a fame of blood. The reinforcements which Field-Marshal French received in abundance he placed round Ypres, but not only for defensive purposes; they were more often used to deliver attack after attack against our young troops who had been weakened by the hard fighting; and on 23rd October they were already being employed in this manner against the 46th Reserve Division.[33] He hoped to use the oppor[Pg 39]tunity of our retirement behind the Kortebeck to break through our line and to roll up the part of the front lying to the north of it as far as the sea, and thus to regain the initiative and freedom of manœuvre on this extreme wing.[34] However, the blow was parried by the 46th Reserve Division. In ragged, badly placed lines the German units, which had scarcely had time to reorganise, brought the hostile masses to a standstill and won back in a counter-attack the ground which they had lost during the night. On this occasion, also, the gunners shared with the infantry the honours of the day. The fire of the guns, brought up into the foremost lines, made wide gaps in the attacking columns and the enemy’s losses must have been terrible. Our own troops had also suffered severely in the constant fighting and under the everlasting hostile artillery fire. Some of our regiments had been reduced to half their strength. But in spite of it the British did not succeed in breaking through between the XXIII and XXVI Reserve Corps.

The XXVI and XXVII Reserve Corps were by this time completely held up in front of strongly entrenched positions on the line Langemarck-Zonnebeke-Gheluvelt and opposed to an enemy who was becoming stronger every day and making the most desperate[Pg 40] efforts to regain his freedom of action and begin a big offensive himself. The XXVI Reserve Corps, which advanced on the morning of the 20th, the 51st Reserve Division from the area west of Roulers, and the other Division from Morslede, encountered a stubborn resistance along the ridge Westroosebeke-Passchendaele-Keiberg. Fighting under the eyes of their general, who was himself in the thick of the struggle, the 51st Reserve Division stormed the slope on to the ridge and enteredWestroosebeke. The French division defending it was driven out at four in the afternoon and, attacking incessantly, the gallant 51st, supported by the 23rd Reserve Jäger Battalion, reached a line from the railway-station north-west of Poelcappelle to Poelcappelle itself during the evening. The attack was all the more daring through the fact that Houthulst Forest was still in the enemy’s hands, and the flank of the division therefore appeared to be threatened. Meanwhile the 52nd Reserve Division had taken Passchendaele, Keiberg and the high ground between them from the British; the artillery again deserving the highest praise for its co-operation.[35] The attack, however,[Pg 41] was brought to a standstill in front of the enemy’s main position at the cross-roads east of Zonnebeke. The XXVII Reserve Corps commanded by General von Carlowitz, formerly Saxon War Minister, lay in close touch with the 52nd Reserve Division on the evening of the 20th. Advancing in four columns and by constant fighting it had forced its way westwards. The Würtemburg Division had succeeded in driving the 7th British Division out of Becelaere after heavy street fighting, and the left wing was bent back on Terhand. Communication was there obtained with the 3rd Cavalry Division, fighting on the right wing of the Sixth Army, which had captured a hostile position north-east of Kruiseik.